Long time no post

November 14, 2011

It’s been a long time since I’ve posted, but it hasn’t been without reason. This year has been extremely busy with performing at school, gigs, and making reeds.

This year in school, I’ve been playing a lot of “the big parts” for the school university. My scholarship requires me to perform with the school ensembles, and I generally enjoy it, but this year has been a bit of a strain. Most recently, I’m performing a new premiere of Charles Wuorinen’s re-orchestrated “Big Spinoff” for 16 instruments. So far, it’s been one of the hardest pieces I’ve ever played, and I’m still not a fan of it. Screaming high F’s, plummeting low Bbs, and some written low G’s and A’s below that, (how an oboist is supposed to play those notes, I have no idea.)

For the school concerto competition I performed the Bach A major Concerto memorized, and got reasonably far. I passed the oboe round, and the woodwind round, but in the final round I had a bad memory slip, and I’m sure this doomed me. In any case, it was a good run, but pretty discouraging.

I’m currently preparing for my recital, hopefully scheduled late January. So far I have Loeffler, Schumann, and Dutilleaux, and I have to add another piece. I’m certainly open to suggestions, so if you have one leave it below under comments.

Reeds are getting pumped out as quickly as I can scrape them. I have helpers now doing more and more work, but I still can’t get them done fast enough. Meanwhile, I’m making some of the best reeds of my life, and feel like I’ve really settled into “my kind of reed”. Flexible, lighter than what I was playing last year, but still full of depth, cover, and warmth. It’s a good place to be.

Back in Bellingham at it again.

July 13, 2011

Well, I’m on vacation here in Washington where I’m taking care of some business. The first line of business was dropping off/catering some reeds for my friend Anne Krabill, and trying out her new Hiniker Acrylic oboe, affectionately titled “The Ice Princess”. DANG was it loud! It was modeled after John Ferillo’s BT oboe and it’s a monster of an oboe. Tom said Ferillo’s Loree has the old de Lancie ream job, and I can definitely feel the relation to that of David Weber’s ream job. Perhaps one was developed by the other or what not. (FYI, the de Lancie model oboe had different tone hole placement than the regular oboes, so while the bore might be similar the tuning probably isn’t.)

Next on the tour was Peter Hurd’s house in Bellingham where I proceeded to try 25 oboes and English Horns.

Some highlights:

- A very nice Covey $4,200. Warmer sound than most coveys I’ve played.

- A BE Loree oboe. Very free blowing and flexible, just the way I like those older Lorees to be.

- Laubin 130. I’m normally not a Laubin fan, but this thing could really sing, and I didn’t feel like it capped me out on the top volume levels like I feel with a lot of other Laubins.

The treat of the litter however was an LI Rosewood Loree English Horn. Man, could this thing rock. Huge sound compared to any of the other English horns, and a really nice warm sound. It was the complete package. Normally with Rosewood instruments I feel like they’re too muffling, but not this baby.

Anyways, I’ll be here for several more days and then head over to Port Townsend to visit Anne. We’ll be oboeing it up, making reeds for her business, and exploring the tiny town of PT!

Occasionally I check in to reedreviews.net to see what people might be buzzing about or who’s reeds are the newest rave. Sometimes I see a new name. Usually it’s the same ranting about so-and-so who makes the worst reeds in the world and yada yada yada. Not to diss my readers, but really. Grow up. It’s not like us reedmakers sit there pondering, “Hm… I wonder how I can promise reed customers the world, then sorrily disappoint them when they decide to purchase…”

While I’ve never officially met her, Jennet Ingle played at the IDRS convention, and played quite well. She has a website which is quite impressive, and her blog is inspiring and a fun read. So when I read a review like this one, which obviously seems to border on personal, I just roll my eyes, and think to myself, “Really? This is the way you want to get back?”

I think every reedmaker who’s been around for a while knows that there are plenty of different oboists, and different reed styles, and one magic reed will not suit everyone. Heck, one reed won’t suit one oboist if they just switch oboes. For someone to expect to get the right reed on the first try is simply unreasonable.

Similarly, I think most professional oboist knows that the reed doesn’t make the man. During the Woodhams Masterclass, he cracked his reed. After the masterclass, I offered him a good amount of cash for the cracked reed for research purposes, which he politely declined, simply stating “It won’t teach you anything! Learn how to play the oboe, not the reed!”

From a business perspective, I switched to subscription orders only because I wanted to build a relationship with every reed customer rather than a one time customer ordering to try and leave. I enjoy corresponding between my reed customers and getting feedback and trying to find the right fit for them. It keeps me on my toes, and keeps me in tune with the needs of every day players.

This summer, I’m finding that my production is quite a ways up, and I’m either scraping faster, or cutting out too many customers, so I’ve opened orders back up to the public. If you want to try my reeds, now is the time to contact me!

Finished the Gouge…

July 4, 2011

Well, it took me a little longer than usual, but I finished my gouge, and boy is it a dandy. I couldn’t be happier with it. Last I blogged about it, I was happy with the opening, happy with the vibrancy, but not happy with the tone color.

- So I thinned the sides. It came out warm as I expected but flat in the top register and the openings were too closed.

- So I thickened the sides. It came out with the same warmth, and a little better in the top register and opening.

- I repeated this about 5 more times, each time adjusting it just a minute or two with the screwdriver. until the opening and upper register was just right, and I still had the warmth.

So, that’s the usual process. Took me probably 50 or 60 reeds but I finally got it.

The main thing you need in order to adjust your gouge is just to be able to scrape consistent reeds. Scrape as you normally would until you can get the gouge pretty darn close to where you want it. THEN adjust your scrape accordingly. But you want the gouge to be catered to your scrape, not your scrape to be adjusted to a faulty gouge.

Still Pondering the Gouge

June 29, 2011

Well, I’ve probably made close to 50 reeds on the new gouge and still am not really happy. It doesn’t have the warmth and roundness that I wish it had, and forces me to scrape in extra warmth by scraping just inside the rails in the heart area, re-balancing the reed so I scrape a hair more out behind the heart and a hair less in the corner of the tip/heart integration line, and I have to thin the sides of the tip. All this is fine and dandy, and doable, but ultimately the more can you are scraping off, the weaker the reed becomes, and the shorter it will last. I have about 50 pieces from the previous gouge and I scraped two reeds up on that, and the reed immediately fell into place, just as I wanted it to, so it confirmed the fact that my current issues are with the new gouge, not my scrape.

One way to get a “warmer” sound in the reed is to thin the side of the gouge. This however can flatten the stability in the upper register, and close down the opening a bit, both of which I’m not entirely sure I want to do. Some 15 reeds ago, I was struggling with a flat upper register. I began making shorter and shorter reeds to compensate and get a more compact product, but the shorter I went, the less resonance and body I began to get so I had to find an alternative solution. I began continuously thickened the sides until I achieved stability. Thinning the sides again seems like I’m going backwards.

So at this point, I have limited options:

- I can settle for what I have, and just continue to rebalance the scrape to achieve more warmth.

- I can minutely begin to thin the sides again in hope for a warmer sound, and pray that the stability won’t drop on me.

- I can begin changing shaper tips, and perhaps use a Weber 1-C is narrower than the Pfeiffer Mack and might give me a more stable register.

- Pull the blade, go for a more oval shape rather than round shape, and get more warmth in the tone that way.

I have some different cane soaked up. Some 1984 Alliaud from Covey that might have different effects so I’ll make my decision if nothing changes after this cane.

Getting the Gouge back in place.

June 25, 2011

Well, it’s been 3 days since I pulled my graf blade to sharpen, and we’re making progress.

Anyone who does their own gouging knows that the biggest pain in the world is to pull your blade, sharpen it, and get it back in the right place. In fact, there’s no good way to do this other than to continuously do it and get practice. I’ve probably done it 30 times and I’m still horrible at it.

Murphy’s law states:

- Your blade will stay sharp for approximately 800-1200 pieces of cane.

- The moment you get the blade in the right position and the gouging machine adjusted perfectly, the blade dulls.

- The blade seems to stay sharp for shorter periods of time as I get better at adjusting my machine.

This is the reason why Martin simply laughs at me for working with gouging machines in the first place. It’s such a big friggin’ pain. Meanwhile, other gouging machine makers have attempted to make machines that put the blade in more consistently such as the Westwind Gouging machine and while I’m still not sure how it helps you put the blade back exactly in the same place, I still don’t see any way around it. If you pull your blade and sharpen it, it will change slightly. It might gouge a little thicker, or a little thinner, but it will change, and any way you look at it, it will need to be readjusted. I think this is one of the major advantages of buying a machine from someone who offers customer service, such as RDG, or Ross Woodwinds. You don’t have to trouble yourself with it.

Once you pull your blade out, you usually sharpen the blade on 4/0 jeweler’s emery sandpaper put it back in so you get the chip thickness to about .04-.06, and get the blade so that it’s centered, then start making reeds. A usual process is like this, except I do everything twice to make sure one instance isn’t an anomaly.

- Gouge a piece of cane. Bend it over my finger and fold it. Wow, that was way too easy and not enough spring. The sides are too thin. Thicken the sides on the gouge.

- Gouge another piece of cane, still a little too flimsy, but let’s tie it up and see what we got. Shaped, tied, tip scraped and clipped. Wow that opening looks microscopic. Thicken the sides again.

- Gouge another piece of cane. The fold feels about right. Shape and tie. Scrape tip open, looks good. Scrape the rest of the reed and try. Round sound, but unstable in upper register. Getting impatient. Thicken sides a good amount.

- Gouge another piece of cane. Fold over finger and it’s a bit stiff now. Shape and tie and scrape tip. Clip open. Wow, I can drive a Mack truck through that. Sides too thick. Adjust the gouge for slightly thinner sides.

- Gouge another piece of cane. Fold over finger and it’s still a bit stiff. Shape and tie and scrape another. Clip open looks good. Scrape the reed, and it just feels a little heavy everywhere. Try, and it feels a bit flat, but consistent from top to bottom. Adjust the thickness of the gouge from .60mm to .58mm.

- Gouge another piece of cane. Fold, shape, tie, and let dry and see what we have tomorrow. Repeat as necessary.

By the time you’re done, you have all sorts of irregular reeds that I give away or just recycle the tubes. It usually takes me between 20 and 30 reeds to get an acceptable gouge. Currently I think I’m around 25ish. So hopefully I’m getting close.

Running a reed business and Reed shipping day

June 21, 2011

There are many advantages about being a reedmaker as a side job.

- You get to work on your own schedule.

- Your business is very portable. You can work from your own home.

- You can work at your own pace.

- You practice a skill which is directly applicable to your main job (being playing oboe).

- Most of the items needed to play oboe (including your knives, reed tools, reed materials, and oboes) can be considered part of the business assets and therefore are tax deductible.

- You always have good reeds.

All of these advantages have served me well, as being a graduate student often requires flexibility in schedule. Sometimes I’ve been scraping reeds at 6am, while other times, I’ve scraped until 2am. My business has traveled with me from Korea, to Oregon, and now to Arizona. There have been days that I’ve gone without making a reed, and sometimes I’ll make 20 in a day.

The tax write-offs saved me a lot of money the first several years, particularly when I slowly started crediting assets such as an oboe or two, gouging machines, etc. over to the business and away from my personal items. My father, being the accountant figured it all out so that over a good amount of time, I didn’t have to pay virtually any taxes for the first three or so years. Other tax write-offs including a portion of internet and cell phone charges, since all of my orders came through either email or phone calls, and even a portion of apartment rent and utilities since I have one entire bedroom reserved for my business.

Perhaps one of the most comforting aspects of running the business is always having good reeds. People always ask me, “So do you pick the best reeds out for yourself and sell off your secondaries?” to which I’m never quite sure how to respond. The truth of the matter is yes, and no.

I make approximately 60-80 reeds a month for subscription, and then another 20 or so for music stores to sell. Of the 80, I’d say 10-15 of the reeds are “special orders”. Some people want reeds a littler harder, some more open. Some like more covered, while others need a sharper reed. I’ve tried enough oboes to know that virtually every oboe has a “special need” to some degree, and I don’t mind such requests as I used to. After scraping all of the reeds, I move all of my reeds, both my cocobolo Howarth XL and Loree, a knife, chopping block, plaque, razor blade and various shotglasses out to the dining room table to give them all a “final blow”. This is the final test to see if they’re all ready to go out.

First I go through the special order reeds to make sure they all fit the bill. Then I go through the rest of and give them a blow and adjustment. Many of them do need an adjustment. A thinning of the corners or sides here, or perhaps a clip there. Occasionally I’ll find one that fails all tests and it gets smashed on the spot, but this only happens once or twice a batch.

Out of a batch of 80, I’ll usually take 5 or so for myself. Regarding the “skimming off the top” question, I guess the answer is yes, I take 5 which fit my oboe and my air and my style, but the term “best” is very subjective. I’ve been around the block and in this business enough to know that my five “best” could very well not be anyone else’s five “best”. In fact, I know that I like my reeds more closed and less “covered” sounding than 90% of my clients do, and so it works out anyways. Furthermore, I’ve tried enough oboes to know that what works in my oboe won’t necessarily work in someone else’s oboe the same way, therefore the reeds I pick REALLY probably won’t be the five best that anyone else would pick. So as for those other 60 reeds that aren’t special order reeds nor the five I pick, they have to pass the following tests.

- Play on both oboes evenly in tone and scale.

- Stable pitch throughout, stable tone throughout.

- Must not be too small in opening and sound. In the Arizona dry heat, if a reed is small here, it generally gets bigger anywhere it goes, but can’t be too small.

- Must not be too easy. I’d guess 80%-90% of the people who buy their reeds, like heavier things to blow against, and spend 90% of their time playing louder than mezzo-forte and don’t value or want a reed which can play a true pianississimo.

- Be very responsive, although this is a given with all of my reeds.

If a reed plays well on one oboe, but not the other, there is generally something false in it which will usually show up when you least want it to (like playing a solo ending on low B and you JUST can’t get that note quiet enough.) I would say nearly 90% of the commercial reeds out there for me require me to control the top register with more embouchure than I prefer, and therefore would not pass my first two qualifiers. I want to be able to maintain an “ooh” focused embouchure at the top register rather than an “mmmm…” smiling embouchure on those top notes. Otherwise, how else can you play passages like Ferling #4 with octaves in tune and clarity in response?

It’s always a great relief getting my monthly reed orders out, and usually I try to do something special like order pizza or go out to lunch to celebrate. Namju and I were rushed this afternoon during her lunch break as we were preparing the orders. She is the official “writer of addresses and packer of reed orders” while I sit at the table sorting and adjusting reeds and selecting which reeds go to whom, so we had to hit Burger King for lunch.

But the reed orders are done, and as you can tell my big reed cases (50 reeds and 40 reeds) are empty, while my two personal reed cases (the black leather with red velvet for the Loree, the wood case for the Howarth) are full of happy, fantastic reeds. Ah, what a peace of mind.

Still processing the lessons learned at IDRS 2011

June 11, 2011

I blog to organize my thoughts, goals, and keep a record of where I’ve come from and where I’m going. It’s more for personal reference than anything else, so if my thoughts seems out of context or disorganized, understand it’s more of an “informational dump” of things that have been working themselves out in my head.

The sounds, performances, and lessons learned at IDRS 2011 are still pushing and poking my daily oboe life in my reedmaking, practicing, and tonal concept. Some things shocked me, some things reminded me of older lessons, some things only confirmed my deep rooted dogmas.

Some lessons learned:

- Dark and covered is a small area of the color spectrum, and while it can be beautiful, it gets boring to listen to after about… 5 minutes. It’s like that wheel of color you get on computers that has every color on it, and all different shades. Dark is just one corner of the entire circle.

- Projection is not how much air you blow through the instrument, but how much resonance, color, and overtones you can allow.

- A smaller, compact, focused sound can fill an entire room.

- What sounds full, beautiful, and complex from 20 feet away, can sound very small, tiny and shrewed from 50 feet away.

- Martin says, “Most players have two dynamics, not too loud, and not too soft.” Even professionals fall into these categories.

- The finest pianississimo’s performed on the big performances at night far outshined the largest fortississimos.

- Even the biggest names can forget accidentals.

- It is a fine line between quick and energetic and hurried and uncomfortable.

- “Playing safe” is like eating a turkey dinner without the gravy. Everything is there, smells good, tastes good, looks good, but there’s something missing that pulls it all together, and you get frustrated that it could just be so much better.

Some things I want to try and strive for:

- Woodhams had such a sleek, streamlined focused sound. It was incredibly flexible, keeping life and direction in the musical line, and could fill a hall. It didn’t sound massive from up close, and it wasn’t terribly covered either, but I would kill for a sound like that.

- Peter Cooper constantly pushed students in the Strauss masterclass for more flexibility, more movement with the line, and more rational thinking for each decision made. While I had thought about most of the decisions he asked about, the level of flexibility he demanded was extreme, and I’m not sure my reeds would allow me to do the things he demanded.

- Woodhams, Cooper, Katherine Needleman, Robert Walters, all had extremely active musical lines that wasn’t just crescendoing up and down, but doing summersaults and loops, defying gravity. The sound would fly off a skateboard ramp straight up into the air and just when you thought it’d start falling back to earth, it’d float away like a little birdey. THIS is what it means to be a flexible musician.

In summary, I need a lot more flexibility, and to plan my musical path through a piece much more carefully.

Back to the grind… back in Loreeland™

June 9, 2011

Well, I’m starting to get back into the daily routine. I gouged, shaped, tied, and started scraping down some 80 reeds, and am getting back into playing shape. I’ve played very little since last Thursday’s masterclass, but I’m feeling the itch to start playing again, so I started today.

After the masterclass, I’ve been keenly evaluating my playing, and thinking about minute details that I did not pay attention to previously.

- How did I tongue that note?

- How long was its duration?

- How was the vibrato on that note? How would a violinist vibrate that note?

- Was the inflection on that note up or down? How would a string player bow that?

- Is it a weak note or a strong note? Is it coming or going?

- Is the finger completely relaxed?

The questions never stop, but I suppose this is the next progression of detail I need to consider in order to bring my playing up to the next level.

I’m back on my old Loree. My Howarth Cocobolo XL is shipped off to Jason Onks to do some major repairs, such as cleaning up some cracks, getting some keys replated, general cleaning and padwork. I knew it needed a lot of work, but this is the first time I have been able to be without the instrument. Coming back to Loree always feels like a “coming home” to me, as I always re-discover subtleties that I don’t feel with other instruments. With a good reed (and I am aware that that is a big stipulation,) there’s a responsiveness, flexibility, and color that I simply never get with any instrument. The differences in color I can play from the quietest of whispers to the loudest of louds is unique to Lorees, specifically old lorees, and I always feel like I’m rediscovering familiar lands I once knew. It’s like one of those awesome dreams where you discover a new room in your house, or you discover a new attic or basement in your home. Ever have one of those dreams?

Tonight I had a woodwind quintet meeting with some friends who just get together to play for fun, and I love playing that Loree in a smaller group like a quintet where I don’t feel like I need a big projecting sound. I can hide, and expand, cover and “gun it”. I usually tell people that my Howarth XL is like a big heavy Cadillac which has all of the power and luxury, but my old Loree is like a little Miata that can weave in and out.

I’m taking this time to come back to the basics, and am working on Gillet #4. I spent an hour and a half just working on the last mordent triplet section at the very end, which gives me all sorts of problems, namely because my technique with forked F is so bad. Throughout practically my entire career, I had teachers tell me never to use forked F under penalty of death or my right middle finger chopped off, (which of course I need it for other purposes than oboe :P). This became such an obsession that I literally lost all use of forked F and could not use it. Several times this year I needed it, but it wasn’t an option, such as the beginning of the year audition on Pictures at an Exhibition. I got through Gillet studies 1 and 2 okay with left hand F, but then #3 is specifically for the use of forked F, and that was a game changer. Perhaps the primary technical concern of mine in that G minor concerto was the forked F 16th note runs in the 2nd movement. Since then, I’m determined to regain control of my right middle finger. So now is the time…

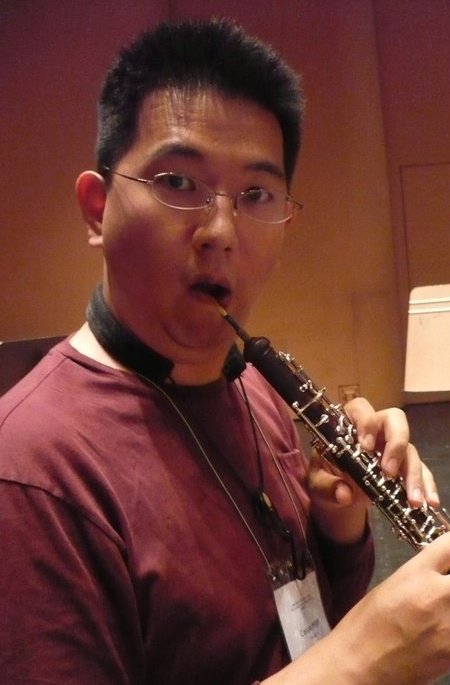

The picture below was taken by my friend Anne Krabill, who convinced me that it would be “fun” playing 3rd oboe in the double reed ensemble on the final day of the conference. I thought I’d be honking out low G’s and F’s. Well, that quickly went out the window as we were bumped up to first oboe and played this ridiculous reduction of the final movement of Gounod’s Petite symphony. Pop out an occasional high E? No problem! An F# here? Why not! What’s a high G among friends anyhow?

The Conference is Over

June 5, 2011

The conference is finally over. It was a lot of fun while it was here, but it’s a lot to take in, and playing a masterclass really juggles up one’s priorities at the conference, or at least it did for me. I missed Robert Walter’s recital amongst several events because I was practicing at the last minute for the masterclass.

I got the courage to listen to the masterclass CD today. I tried to last night, but it was the combination of being utterly exhausted and still feeling quite raw that caused me to turn it off after a few minutes. The recording of the masterclass wasn’t as bad as I expected, and after listening to a couple parts here and there, I finally began to pick up on what he was exactly trying to demonstrate. It was very subtle, and it took repetition to finally figure it out, but I understand now.

I’m always jostled when I hear a recording of myself play, namely because I never hear myself from any distance other than the 6 inches from the instrument to my ear, and because oboe records so badly. After I heard the first sound on the CD, I immediately turned to my oboe friend and asked, “Do I really sound like that?” to which she reassured me I didn’t, but it still makes me think about projection, and what overtones don’t carry vs. what overtones project. If I had to do it over, I would have definitely gone in with a reed that was less covered/fat sounding, and chose something more compact, leaner, and flexible. The reed I was playing was a bit thick, and I had a bit of difficulty with articulating the notes EXACTLY how he wanted it. I intentionally chose to play on a reed with better tone because it was only a month ago I played my jury in there with a reed that didn’t have enough tone and it left me sounding small and tight. Decisions decisions decisions. I think the current sound I am projecting is fatter and more covered, but less clear. Playing next to Woodhams and hearing the recording of the masterclass, I realize that the sleek core of his sound carries to the back of practically any hall, but much of the complexity of his sound gets lost in the compression of recordings, which is a darn shame.

So I tried a handful of oboes this year, and truth be told, I wasn’t overly impressed with any of them. The best of the lot was a Marigaux 901 with the last 3 digits of 346. Perhaps I’m just happy with what I have, or perhaps I’m just not as crazy about shopping for the perfect instrument. The Yamaha 841 kingwood lined still feels good but the ones I tried felt small this time around. I did get to meet fellow reedmaker Jonathan Marzluf, who had an awesome Grenadilla Hiniker oboe. Drool. I didn’t remember my Hiniker being anywhere near the quality of his, but I guess that was a year ago.